By Laura Nepodal, SFG

![Screen Shot 2013-03-04 at 7.38.50 PM]()

I think I knew I wanted to be strong when I threw a boy for distance for the first time.

It was June of 1997, in a little basement of a little farmhouse in a little farming town, out in the middle of the sprawling fields of Iowa. A handful of ten-year-old boys—plus one girl and her little brother—had infiltrated the sweltering subterranean space to secretly watch the Holyfield vs. Tyson fight. It was to be a battle of immense proportions—who would possibly want to miss that? Yet there was time to kill—inferior mortals were in the ring, delaying the battle between the lords of the boxing world.

And what do ten-year-old boys (and one girl) tend to do when left restless, unsupervised, and with access to glorified violence?—They wage their own epic battle, of course.

Amidst the tussling and screeching that filled the basement, one shrill squeal rang out from the aforementioned little brother as he was helplessly pinned by one of the older boys. So ten-year-old me walked over, picked the boy up off of my little brother, and tossed the said boy across the room. The boy turned to look at me, wide-eyed, and said, “WOW. I was just picked up and thrown by a GIRL!”

You bet your booty you were, buddy.

While we all left with our ears intact that day, I think I left with something equally as valuable: an appreciation of being able to handle myself. An appreciation for being strong. (Although I may have been equally inspired upon hearing my Israeli cousin’s profound statement, “Be strong like cow.”)

Like all things that are worth understanding and integrating into our lives, strength is a multifaceted concept. There is the nearly unfathomable strength that we witness in extraordinary situations—the bravery of a five year-old girl fighting for her life against acute leukemia, and is able to thank God for being her healer as she lies on a table receiving full-body radiation (my sister fought and won that battle, and continues to be one of my very greatest inspirations). More often, we witness strength in its more subtle forms daily—in the quiet displays of willpower and accountability that we consciously instill in our everyday choices when no one is watching.

And, more notably, I feel, is our ability to push past our own inertia. Inertia is grounding, safe, known. To breach that barrier and push past our comforts, to begin the process of surpassing our own expectations of ourselves, is the most difficult step. But you start to find that it was the first step that was the hardest. The potential of —or rather, the fear of— failure, is no longer so insurmountable. You have the momentum of your bravery, of your strength, to carry you forth. And when you hit that inevitable bump on your path that could slow you down, the foundation of strength that you’ve nurtured will help you to maneuver that obstacle – or, you know, totally crush it into oblivion because you’re just THAT strong.

Women, enter the most honest and least prejudiced judge of strength you’ll ever meet—iron. Iron will never lie to you, never coddle you. You will love it, spend a great deal of time with it, and occasionally become angry or frustrated with it. But it will not waver, and it will always hold you accountable. When you clean a kettlebell to the rack position with the intention to press it, or set up to deadlift a loaded barbell off the ground, the iron expects you to push past its inertia. It expects you to be strong. It demands it.

In a society that doesn’t have a history of lauding the physical strength and prowess of women, our collective inertia is substantial. We are told from a young age that girls can’t do push-ups/pull-ups, that full-contact physical activities weren’t meant for us, and that we are generally weaker in relation to men. Standards are set lower for us, and so collectively, our general inclination is to aim low, or to maybe reach that silly, low-slung standard.

Because to go beyond that would be to push through our own inertia, and that’s just freakin’ hard. It takes internal reformation of the way we perceive ourselves; a complete restructuring of the way we view strength in relation to ourselves as individuals; and a strong sense of self in a society that doesn’t tend to celebrate us when we achieve something iron-STRONG.

In other words, it takes a lot of the strength mentioned earlier, a lot of mental toughness (see Master SFG Instructor Mark Reifkind’s impressive blog on this topic, applicable to all), a passion for self-betterment—and maybe a little desire to squish those silly, predetermined limits that we women have allowed ourselves to be yoked into. It is also immensely helpful to have a community of like-minded brothers and sisters in iron to learn from, inspire you, and help you along the way. StrongFirst is that for me, as well as for a plethora of incredibly gifted, talented individuals.

When a woman takes her first conscious step towards being physically capable and more–past her inertia—she immediately expands her limits of possibilities—because really, if you’re going to contradict what society (and yourself, up ’til now) have told you that you’re capable of, what other awesome stuff can you accomplish? Not to mention that being strong will make many other pursuits of the physical variety significantly easier and more enjoyable. Train hard to play hard.

You may not start strong: you may not be able to do that full push-up yet (death to the so-called “girl push-ups”, I hereby decree the demise of that belittling name!), complete a bodyweight pull-up, press a 12kg kettlebell, or deadlift your bodyweight—but oh, barring extraneous, isolated scenarios involving medical maladies, if you put in the time and effort, hone your focus, and apply the StrongFirst concepts to your training, you CAN get there.

As one of my favorite authors, Paulo Coelho, profoundly stated, “In order for us to liberate the energy of our strength, our weakness must first have a chance to reveal itself.” You can only be strong if you know where your weakness lies—so acknowledge your weakness, thank it for showing you the way to the new, improved you, and then surpass it. Do not simply seek to meet the standard set before you; strive to crush it. If only for the thrill of the chase and the inevitable self-betterment, self-empowerment, and all-around increase in physical health and holistic well-being, do not aim for less for yourself! You will look good, feel great, and be strong as hell.

The only thing stopping you from pursuing and achieving this is fear, laziness, or apathy—none of which, in my most humble opinion, should be acceptable qualities that you nurture in yourself.

At StrongFirst, we know what women are capable of. The bar is not set low for men, and it certainly isn’t for women, either. Once you have made the commitment to embrace and pursue your strength, what is the standard you should strive to reach, or for the exceptionally strong or ambitious, to surpass? What makes a woman “strong”?

A strong woman might be able to successfully complete some, if not all, of the following:

- Three bodyweight pull-ups

- 1/3 bodyweight military press

- 1.75 bodyweight barbell deadlift

- 1/2 bodyweight get-up

- 1/2 bodyweight swings for reps

Why strive to be strong as hell? Because being physically strong is incredibly liberating, very healthy, and immensely empowering. When you train smart and train strong, you add longevity to your quality of life, make every other physical task easier, and gain an intense, burning curiosity to discover what you’re capable of. At first, you may look at a weight you deem too heavy and shy away from it. Once you have whetted your appetite

with the taste of success, you will begin to look at that same weight and think to yourself, “I bet I can do that…”. When this happens, and you have attained a strong understanding and mastery over the skills and techniques of strength and safe training that SF teaches, you are well on your way to becoming strong. Nurture that ambitious curiosity. It will also will transfer to other parts of your life.

To some, the above numbers may seem unreasonable or too excessive. I feel they’re an honest representation of what women are capable of, knowing there are many very strong women out there that can surpass these numbers.

Yes, minus the extraneous mutants that are out there, getting strong is hard. It takes intense commitment, time, focus, and a hunger to learn. Many women having a misguided understanding of what training heavy does to the female body (we only have so much testosterone at our disposal, ladies; a huge, Schwarzenegger-type physique is not an option for us without supplemental assistance), and a skewed perspective of what a high-volume, low weight protocol can do for their physique (there is no such thing as a “toned” muscle, or a “long” muscle; your muscles are the length they are based on the skeleton they’re attached to, and a low body fat percentage will give you that sought-after sculpted look, which lifting heavy effectively helps with). Educating ourselves, and nurturing the necessary fortitude it takes to be strong, are the first steps. There are many women out there that have yet to embrace and forge their own strength for fear of failure. Ladies, we must all start somewhere.

So let’s start somewhere.

Firstly, I would very strongly recommend that you seek out a certified StrongFirst instructor to assist you with your technique, and to help enforce the principles of strength that we effectively utilize. There is no substitute for good coaching done face-to-face. If that is not an option for you, that’s okay—the StrongFirst forum is a great way to get some feedback on your training.

Ideally, you will have access to kettlebells and a pull-up bar. If you are a bit more advanced in your training, access to a barbell would be ideal, as well. Pull-up practice, swings, get ups and military presses are a good place to begin, with the addition of barbell deadlifts for those who are a bit more advanced.

Pull-up Practice

If you have a difficult time completing a pull-up, do the following: Install a pull-up bar in the doorway to your living room, bedroom, or another frequented room (mine is in the kitchen). Whenever you walk into that room, jump up to the pull-up bar so that either your neck or chest are touching the bar, and then slowly lower yourself through the negative portion of the rep. Just one rep is enough, as you will be walking into this room more than once a day.

If you are unable to perform this without assistance, have someone push your mid-back with just enough pressure to help you to the top. If you don’t have a training partner, you might find the use of a stretch-band to be helpful. If you do use stretch-bands, be sure to place a foot in and stand on the band, versus kneeling in it; I feel the kneeling position tends to promote lumbar extension, making the ideal hollow position impossible to

achieve. Though stretch-bands have a tendency to offer assistance in the part of the pull-up that isn’t most people’s sticking point, it does enable you to get to the top of the pull-up and work this position. Within a few weeks, you will notice that this is much easier than it was when you started.

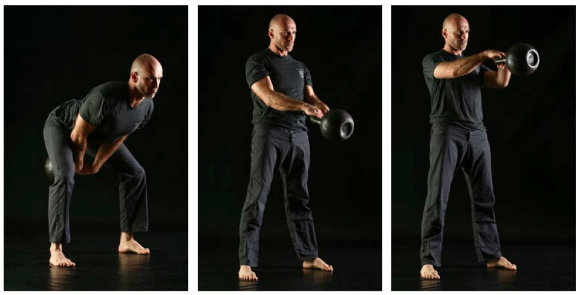

Swing

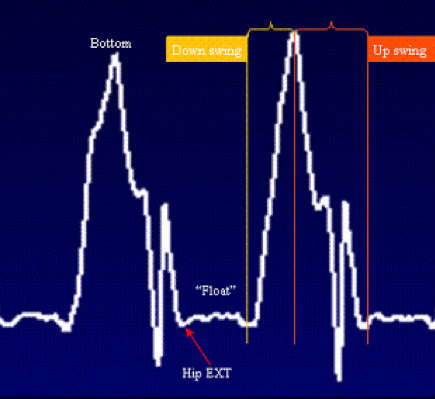

The kettlebell swing is an excellent option for conditioning, as well as for all-around strength. If you are just starting out, depending on your athletic background you may want to use an 8kg or 12kg kettlebell. Eventually, these weights will feel too light for you. At first, keep the reps low—you want each repetition to be explosive, powerful, strong. When you feel your form start to slip, stop. Perform sets of no more than twenty swings; if that feels too easy, then up the weight, if you can do so and maintain proper form. Doing powerful swings, and eventually heavier ones, will condition you, strengthen your grip and abdominals, and give you a strong, shapely posterior. Eventually, doing heavy swings alone will make your barbell deadlift much stronger (my own barbell deadlift 1RM increased by 30 pounds after a three-month hiatus from deadlifts by swinging nothing lighter than a 32kg during my workouts). So remove thyself from the disgrace of frequenting the hamster wheel, and swing a badass ‘bell instead.

Turkish Get-Up

The get-up is a strong way to work the shoulder stabilizers, and effectively targets many muscles groups in one movement. The get up should be performed with no weight at all until proficiency of the movement is achieved, and should be done with careful intention, without the utilization of momentum—this is a grinding movement, requiring strength and focus. Perform 3 sets of 3 repetitions, right and left, with no weight at all to start, or a weight that is moderately difficult when your skill level has deemed the use of a weight to be safe.

Military Press

Military presses are a good counterbalance to your pulling practice—and the practice of both will make the other skill stronger. Use a weight that you can press 3-5 times without turning the movement into a push-press, and perform 2-3 sets in a workout. When you get bitten by the strength bug, you will want to up your weight; as Pavel has been known to say, “To press a lot, you must press a lot”. So press frequently, using a weight that is

moderately difficult.

Barbell Deadlift

If you are a bit more advanced and have access to a barbell, I highly recommend doing deadlifts. Pavel has outlined numerous times the benefits of the deadlift for strength gains, its ability to transfer to many other lifts and everyday activities, and its ability to target so many muscle groups at once. Plus, there’s nothing quite so satisfying as lifting a lot of iron off the ground. Be sure to keep the weight light until you are able to complete the movement correctly—without using your low back, keeping your abdominals and lats connected and engaged, and pulling from the hips. (Many find it useful to envision pushing the feet down into the ground, as though you’re attempting to push the earth way from you.) With the deadlift, as with other grinds, you don’t want to do too many repetitions in a workout. So keep the reps low, and the weight at least moderately challenging, to achieve the greatest benefits of the lift.

This is just the tip of the proverbial iceberg, my sisters. We all start somewhere, and I believe this is a good place to start. But of course, this isn’t actually where you start—that first step is yours to take. Before you can press, pull, or manipulate iron past its own inertia, you must conquer your own. It is just the start of an invigorating, glorious, epic journey, that first step. And that’s what strength is—a journey. So surround yourself with those who are stronger, more educated, more advanced, and listen. There is no excuse not to start now, no reason to fear your strength. Embrace it: the time has come to liberate the energy of your strength.

# # #

Laura Nepodal, SFG is an avid rock climber, deadlifter, and student of strength. She is also an academic student pursuing her degree in Kinesiology, with the intent of attaining a doctorate in Physical Therapy. You may reach her by email at lauramnep@gmail.com, or visit her website at www.classicironkettlebells.com.